Resilience Study Examines How People with Disabilities Live Successfully in Rural Areas

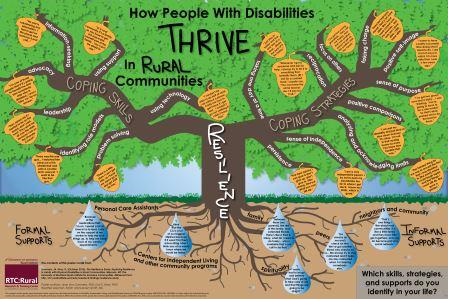

Resilience Study Tree (PDF available upon request) | Resilience Tree Image Description

Resilience Study Tree (PDF available upon request) | Resilience Tree Image Description

May 17, 2017 - Living in a small town can be challenging for anyone — but for people with disabilities, rural areas can create even more serious barriers to accomplishing the things they want to do.

However, with the help of a trait known as resilience, many people with disabilities who live in rural areas have achieved a good quality of life and are able to participate in their communities.

“Some people do well in life because they face few obstacles to meeting their goals: they are healthy, they have parents who are well-educated and have the resources to provide their children with a good education, and they have the support they need,” said Jean Ann Summers, research director at the University of Kansas Research and Training Center on Independent Living (RTC/IL).

The Resilience Study – which is still ongoing – didn’t focus on this group of people, though.

“Other people do well in life despite the obstacles that they face. They may have grown up poor, they may have a disability, they may live in a community where few jobs or other opportunities are available. And yet they thrive. They are able to achieve their goals and have a satisfying life in the community in spite of the odds that are against them,” Summers said. “We say those people are ‘resilient.’”

Summers and her collaborators Dot Nary, assistant research professor at the RTC/IL, and Heather Lassmann, graduate research assistant, set out to identify what Summers calls “the secrets of success” that resilient people with disabilities employ to successfully live in rural communities. Their work is part of larger project based at the University of Montana Research and Training Center on the Ecology of Rural Disability.

“The study is important because if we can find out what people who are naturally resilient do, we can design a program to teach others how to be resilient,” Nary said.

According to Summers, the thought process behind the study is much different than the approach medical or health care practitioners consider when trying to support people with disabilities or chronic illnesses.

“For example, in the medical model we would approach ‘fixing’ a broken leg by putting a cast on the leg,” Summers said. “But a resilience model would focus on what it takes to make that leg grow strong, with the right nutrition and exercise, to prevent further breakage of those bones in the future.”

The study applied this model in two phases. First, researchers conducted two focus groups of people living in rural communities who were nominated by staff at centers for independent living (CILs) as people who display resilience.

“In the focus groups, we asked the participants to talk about the supports that were helpful to them in enabling them to participate fully in the community,” Nary said. “We also asked them to talk about any attitudes or philosophy that helped them succeed in reaching their goals.”

The researchers used what they learned in the focus groups to identify a series of supports — both formal and informal — along with coping skills (such as advocacy) and strategies (such as humor or focusing on others) that contribute to a person being resilient. They illustrated these findings in a tree-shaped graphic, which identifies the roots and branches that contribute to resilience.

In the second phase of the study, now ongoing, the researchers partnered with their colleagues at the University of Montana, who had conducted a large-scale national survey of people in rural communities. Using that survey data, they identified a new group of people with disabilities who they defined as resilient because they (a) had more than two risk factors (i.e., obstacles to success) and (b) their survey responses indicated they were successfully participating in their communities.

Summers and Nary are now interviewing these individuals by phone to get a deeper understanding of what contributes to resilience. “We are hearing things that are similar to what we heard in the focus groups,” said Summers, “but we’re also looking at other personal or environmental factors that contribute positively. For example, a particular city may offer unique environmental or social features that make participation easy for people with disabilities.” That report will be completed in late 2017.